Press Freedom Day

In Eritrea, Jailed Journalists Continue to Languish

In Eritrea, many journalists have been held for more than a decade and denied access to lawyers or family members. Despite positive changes in the region, the country continues to hold the unenviable title of the worst country in Africa for jailed journalists.

'Fake News Crippling Media's Role of Enhancing Democracy'

Former Zimbabwean journalist Miriam Sibada says fake news is chipping away some pillars of democracy in some societies at a time when citizen journalism has taken center stage in circulating true and false information. VOA Zimbabwe Service’s Gibbs Dube speaks with Madziwa about this and related issues.

Gibbs Dube (GD): What’s your take on media and democracy in times of disinformation?

Miriam Sibanda (MS): What I am seeing and finding very worrisome is the fact that there is so much information floating out there, but it is taking away from democracy. So instead of enhancing democracy, all this information - the fake stories, the disinformation - is actually working against us, and the media is no longer able to play its intended role which is to education, inform and entertain, because how do you educate your readership or your listeners when you are dealing with false information. What you are instead doing is racketing up emotions, you are denying people a chance to critically engage with issues, because the starting point is not solid as it were, because now there is all sorts of information there and unlike in the past where you read a story, listened to a news bulletin, you could make a decision. I think a lot of us now, your sixth sense tells you after you have read something, is to say, mmmmm, is this true, is this correct, and you find that you are having to fact check before you can decide or even pass on the information, to anyone or use it, for whatever purposes that you intend to use the information you are reading, an article or listening to an article, for. So as a result, its taking away from the intended purpose of democracy where you are supposed to make informed decisions. How do you make informed decisions, when you are being informed by lies, as it were.

GD: so now looking at filtering this kind of information, how do you tell that this is fake news? And for a common person, how do they do that?

MS: It’s not easy to tell. I’ll be honest with you, even myself, you know, a trained media person, I have fallen for fake news several time. But with time now, you learn, if it is a written article, you are checking for spelling mistakes, the grammar, the presentation, and once you pick those tale, tale signs…but there are others who have perfected the art of fake news, so you then have to go down to consistency – does this make sense, is it flowing? But sometimes you will find, some of the stories might not make a lot of sense, but they turn out to be true, and this is emanating from the fact that you also have, you know, this trend of citizen journalism, where people are seeing things and they are reporting on them, but they don’t know how best to do it, and sometimes the information is presented haphazardly, and there is the danger that you can mistake it for false news, when in actual fact it is true and factual, just not packaged right.

GD: So is there any way citizen journalists can may be used for the sake of enhancing democracy, and even common journalism itself, can it be used somehow, now, since you are saying that you know, you can no longer trust sources of news. So how can this be all integrated to come out with some truthful information, circulating out there?

MS: I think we have to go back to the basics, starting with those who are trained for the job, to just say, you know, address the 4 Ws and H, as best you can. And the citizen journalists, they need to be taught, they need to enhance their skills by reading and listening to those that are trained to do it. And I think the simplest starting point is just working with the truth. If it is two people that you have seen engaged in an accident, or in a fight, let it be two and not be ballooned to scores of people. You know those basics – if we start there, we are giving people the correct information and then from there, they can make informed decisions.

But I think there’s also need to just go all out to train our citizens on how to relay news or information, so that it benefits all of us, and just make people aware that lies will not help us at all.

GB: Going forward Miss Madziwa you know that it is very difficult to train everybody to understand the art of disseminating information. With everybody being a journalist, how best can this be done in order for people to get true information.

MS: I think it has to start with each individual just saying, you know what, I will try to tell this as best as I can, as truthfully as I can … Try and leave out the emotions, try not to exaggerate and just say this is what happened so that the other person gets the correct context and understanding of what it is you are talking about. And it is audios and video clips let they be clips that give context and meaning to what you are raising. That way I think we make a start but I think those of you who are still practicing, you have to take it upon yourselves to bring on board these citizen journalists and help them learn the art of telling a story and telling it as truthfully as possible. Let truth be the starting point and then the other details can follow later.

GD: Can politicians play any part in this kind of news dissemination in order for societies to get the truth out there?

MS: Yes, I think everybody has a role to play. With our politicians I think the starting point is just consistency in their messages because one of the things has to happen is the confusion from the minds of the reader arises from politicians who blow hot and cold depending on their audience. So, if politicians can be consistent in their message, we are not saying they should use the same words or whatever but the messages must be consistent so that if then they are reported to be saying something out of turn the readers and listeners can say hmmmmm this does not sound like our leader, doesn’t sound like the person we voted for and then they go out of the way to try and find out whether he was quoted correctly, the story was written in context. So, it really just starts being consistent with the messages they give out on the various issues that they decided to engage in or engage on.

VOA Africa Division Director Speaks on Press Freedom and His Journey From Ethiopia

In observation of the 2019 World Press Freedom Day, VOA Africa Division Director, Negussie Mengesha reflects on his beginnings as a journalist in Ethiopia, and how he fled from persecution from the government, ending up in a refugee camp, and then arriving at VOA.

World Commemorates Press Freedom Day

World commemorates Press Freedom Day ...

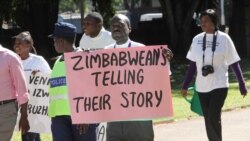

Zimbabwean Journalist Joins World in Marking Press Freedom Day

Zimbabwean journalists have joined the world in marking Press Freedom Day. (Video: Gibbs Dube)

World Marks Press Freedom Day

World Marks Press Freedom Day. (Video: Gibbs Dube)

VOA Director Says Free Press Key in Crafting, Preserving Democratic Societies

World Press Freedom Day is this year jointly organized by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the African Union Commission and the government of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. According to the United Nations, the main event is taking place in Addis Ababa at the African Union Headquarters. This year's theme “Media for Democracy: Journalism and Elections in Times of Disinformation” discusses current challenges faced by media in elections, along with the media’s potential in supporting peace and reconciliation processes. World Press Freedom Day was proclaimed by the UN General Assembly in December 1993, following the recommendation of UNESCO's General Conference. Since then, May 3, the anniversary of the Declaration of Windhoek is celebrated worldwide as World Press Freedom Day. The United Nations says this is an opportunity to celebrate the fundamental principles of press freedom; assess the state of press freedom throughout the world; defend the media from attacks on their independence; and pay tribute to journalists who have lost their lives in the line of duty. VOA’s Salem Solomon Fekadu speaks with Amanda Bennett, VOA director on press freedom.

SS: All right, thank you so much for a sit-down interview and for making time today to speak to us about press freedom. To get started, I would like to get your perspective on why press freedom matters?

AB: Well, you know, here in the United States, we say that there's it's not an accident that freedom of the press is the First Amendment of the Constitution, because unless you have free press, which means something that can independently bring information to people, you can't have a democratic society. And you can see around the world when governments are in trouble or doing something that the people wouldn't like when there's takeovers, coups, elections that are contested, that's when they close down the press. Why is it? It's because they realize that information is power. And if the people get too much power, they'll be able to balance out the power of the leaders. And that's why they closed down the presses to keep the power for themselves.

SS: And there's a lot of battles over truth right now, globally speaking. And it seems like it's on a daily basis. And I think most people would agree that the free press and following the tried and true journalistic principles is very important, because of what you just explained. But where does the Voice of America stand in this?

AB: So for 75 years, the Voice of America has had is its mission to bring objective, verifiable news and information to countries that don't have any other way to get it. So we broadcast into some of the most closed countries in the world. You know, it's just shocking to realize that only about 13 percent of the countries in the world even the people in the world live in countries where they have a free press. So that's the audience we serve. And we think it's important that people have access to information they can believe.

SS: And from your work, and you've been here for a while, what are the challenges that you hear from our journalists?

AB: So the people that are working in these countries where there is no free press, are facing exactly the same kind of conditions that the people in the domestic markets are having. So they're having to deal with the fact that, people try and shut them down, people try and take their equipment, they get beaten up, they, you know, we don't have anybody to think thank goodness, we don't have anybody in prison right now. But they face the possibility of being detained. So they're facing the same kinds of threats that the local journalists are. And we depend completely on these really courageous journalists in the countries we cover.

SS: And you've been on the ground in Africa, you've been to Nigeria, you've seen how our reporters on the ground operate. You've been to the Central African Republic, what are the challenges that reporters tell you that that comes in between what they do on a daily basis?

AB: So I was able to meet with groups of journalists in Uganda, where they are, you know, a lot of them had been beaten up in the course of doing their work, I was able to meet journalists from all over Africa, various groups that we've put together. And they talked about the problems of working inside a media system, where so much of the broadcast capability is owned by somebody with the agenda. So they were saying, you know, we can be the best journalists in the world, we can report the best story in the world, but we can't get anybody to run it because the person that owns the station, won't let it go on. So that was a huge problem. And another problem is that journalists are paid so badly in Africa that, you know, you try and get away from the brown envelope culture because you know, that is really completely off-limits for journalists. But they were saying, like, we don't get paid enough to live on. So it's a real struggle for them.

SS: You also met a lot of women during the course of your travel on the continent, what do they tell you? What kind of experiences today share with you that really struck you, that really resonated with you?

AB: You know, what really resonated with me as to talking about talking to these journalists reminded me a lot of the situation that my friends and I faced, actually, about 40 years ago, it was very similar, where there were so few women, the expectations were that you couldn't do it, there was really a big resistance to having you out there. And so they were talking about how you overcome that. And it made me remember about, you know, my own past when, when it was a really very unusual thing to have a woman journalist, but at the same time, a lot of the struggles that they were having felt very contemporary, they were asking, like, you know, what do you do about your children? You know, how do you explain it to them? What about the family, they expect you to cook dinner, you know, so they have a lot very contemporary experiences as well. And I was I was really thrilled to be talking to because you could see they were thinking through about how they could have a good career.

SS: And other, aside from censorship, and, you know, monetary challenges, also governments try to stifle information, which is really true to our mission. So when there are efforts to stifle information, how does VOA get around to make sure that we get balanced and and and, you know, information out to our target audience?

AB: Well, that's one of the things when you're talking about the journalistic standards, one of the journalistic standards is to try and figure out how you can verify things and how you can talk to different sides of the argument. So, if one side isn't talking to you, you can often find out things from the other side, and you can balance it out like that. And then there's also being able to verify things, factually, that's a really important thing that we try and do. And that's, I think, an advantage we have with having a big operation here back in the United States because the journalists here can help the journalists on the ground get the additional information and factual verification.

SS: So it's an advantage to be here. One of the example that I really speaking of all sides, that really struck my attention when we're working on Burundi. Burundi is a perfect example where the government has shut down the BBC and our broadcast. And we reached out the government to ask, what is the reason and they forbade him, the presidential advisor said, ‘because of fake news’, it was very interesting to me to hear from a foreign government to say that we're that, you know, that's why they're doing it. What's your take on those kinds of excuses, I would say, to stifle information?

AB: I think that the use of the term fake news is really unfortunate, because you as a journalist know, I know that if it's fake, it's not news. And to use a phrase like that, that's really an empty phrase, to shut down legitimate newsgathering operations, wherever they occur in the world. That's really a tragedy. And you know, with Burundi, we got shut down. And there were various excuses given to us to BBC, that honestly really didn't, didn't hold water, they weren't, didn't seem to be really true, it was that they wanted us out. So they just made up these excuses. So that's the kind of thing you see happening. They don't want to say what their real reason is.

SS: So it's becoming really harder and harder, especially in authoritarian governments, where either they deliberately suppress information and they or they banned completely, but it's harder for them also, to do that, because people can share videos on social media, it's more accessible now. I think the more the problematic thing right now is the effort to disinform, meaning, you know, I don't want to say fake news, quote, unquote. But there's that effort. And so what are we doing to at least, you know, have we're an effort to have people filter information, what are we doing from VOA?

AB: You see, I think it's really important when you're facing a climate where people are from various countries are trying to make sure that you get caught off balance that you don't believe that there's the truth, you don't believe things you, you get confused about whether even is the truth. And we try and make sure that everything we do is verifiable. And so I think that gives audiences a way to at least know that if they reach a trusted news source, that they can have an idea that what we are broadcasting is as close to the truth as you could possibly get. So I think we've I feel like we're kind of a little anchor in the storm, and that trusted news organizations are increasingly going to be that kind of an anchor when all this other stuff is floating around.

SS: So a place where people could come to confirm. So do you see, I mean, we talked about the challenges, but what other opportunities, I feel like this is an opportunity for people to come and say, yes, VOA a said VOA said this so it must be true kind of confirmation, are there any other opportunities for us to look into to fill this gap that is new, and unfortunately, in Africa, really rampant?

AB: Well, and you also see the opportunities lie in the fact that people do actually want news they can believe. I mean, I think some of the authoritarian governments try and tell us that, that the, you know, this information is just going to confuse everybody. But you do see that when something terrible is happening, let's say, let's say, you know, inside of Iran, we can watch our traffic going up people are, even though it's against the law for them to see us, they find ways to get to us, when you see when their area really important things, let's say what's happening in Venezuela, you can actually see our traffic in China, go up where people want to try and find things. So even in places where the news is the most controlled, you see that people's behavior, particularly digital behavior, which makes it a little bit easier to get to it. They're trying to find news that they can believe in, which I think is a really hopeful, hopeful sign.

SS: ...they'll find a way to get the information. Another angle that I really want to touch from your personal experience, you've worked in China. What was it like because there's an effort of China and foreign governments and China and other governments to come in and have a soft power footprint on our continent. I'd like to hear your perspective on your personal experience working in China.

AB: Well, I was in China a very long time ago. So I got to see sort of an original way that China operated. And the news wasn't really news, what it was, was the daily feed of what the government wanted you to think about that day, and there was no pretense about it, it was, you know, here's what the important messages from this Chinese Communist Party and that you should be thinking about. And so the fact that it was really, really tailored to what they wanted you to believe, had really very little to do with actually the reality on the ground. I remember doing a story where, I, back then, I kind of like fact-checked some stories that were in the People's Daily. And it was so funny because there weren't, there were no facts at all. You went and looked at each one of them and tried to find them. And you could never find anything. It was all storytelling.

SS: Were there any specific angles that they didn't want a maybe the Communist Party didn't want to hear? Sometimes, you know, these authoritarian government or certain party, there are certain stories that they don't want reporters to write about. Were there any difficulties like that?

AB: Well, those things changed from time to time, depending on what was going on. You know, a more modern example I can show shows both what they don't want you to know. And also what happens when people find out. I don't know if you remember, there was the crash of the high-speed train just outside of Shanghai several years ago. And the government said there were no injuries. Nobody was killed. Nobody was hurt. No problem, no big deal. The people around there. They were it was an urban area. They saw the casualties. They saw that people had been killed. And they were so outraged that they went to Twitter and whatever the Chinese equivalent of Twitter is the and put these stories out that said, this is not true. We saw dying people with our own eyes. And that's a real danger when the government puts out the narrative about something, but people can check it with their own eyes, that really does create an impression with people.

SS: What is VOA stance in terms of, you know, reporters, for instance, as you said, like, you know, even if you're not a journalist, when you are exposed to information that the government or it really party and authoritarian government doesn't want you to see you face danger. And I think VOA is very clear about that kind of, you know, consequences. We've had reporters slain and line of duty, you want to talk about a little bit about, you know how dangerous it is, for instance, for our reporters on the ground?

AB: Well, it's very dangerous, because they face we just had a journalist killed last year and Somalia by a while he was working while he was covering a story when a car bomb went off near the story. So they're facing the ordinary, the ordinary, but tragic dangers of their own societies where car bombs are, you know, being targeted to public places. But then they're also facing the possibility that they will be specifically targeted by people who don't like their reporting. And we see that all around the world that journalists who say trying to uncover corruption are particularly vulnerable to individual targeting.

SS: One last question I'd like to ask you, you are heading this really important project about press freedom, it's very important to VOA and you, you're very invested in this. People would like to know what that project is about why it's it's so important to you?

AB: Well, we say that VOA represents press freedom around the world. And so we all thought it was really important that we make an effort to cover the stories of press freedom, so that we begin to cover the stories that show all the various ways not just jailing, and killing, but all the various ways that information is controlled, so that people can start to see what kinds of things are happening to keep them from the information they know, they should know. And also to try and show kind of ways that people can reach out for press freedom. It's not always just as closing down. Like for example, in Ethiopia right now it's going exactly opposite. With the new leadership there. They're opening their opening out the press area. And so we want people to see a full picture of press freedom so they can decide for themselves how important this is to them.

SS: Well, that's that's it for me. But if there's anything you'd like to add about, about press freedom.

AB: Well, I thank you very much for doing this interview. Because as I say, we actually believe that press freedom is actually the essential thing for a democratic society. Because if the people can't see here and trust, what information they're hearing, then they have no power in and without power without the people having power. You can't have a democracy.

SS: On that note, this concludes our interview. Thank you so much for making time again. I truly appreciate it.

AB: Thank you so much. I really appreciate being asked.

Afrobarometer: Popular Support for Media Freedom Drops in Africa

Popular support for media freedom in Africa has dropped to below half of adults, according to a latest survey conducted by Afrobarometer.

In the sixth of its Pan-Africa Profiles series based on recent public-opinion surveys in 34 African countries, Afrobarometer reports that media freedom supporters are now outnumbered by those who believe governments should have the right to prevent publications they consider harmful.

Declines in support for unfettered media were recorded in 25 of 31 countries tracked since 2011, including steep drops in Tanzania (-33 percentage points), Cabo Verde, Uganda, and Tunisia. “While many Africans believe that media in their countries have more freedoms today than they did several years ago, this is more often seen as problematic than as progress, the data suggest,” reads part of the report.

The new report also analyzes Africans’ news habits, showing that radio remains ahead of television as the most widely accessed source of news. “Use of the Internet and social media as news sources is expanding, but a large digital divide still disadvantages poorer, less-educated, older, rural, and female citizens.

“Radio is still the most widely accessed source of news, followed by television, while newspaper readership remains relatively rare on the continent. Access to Internet and social media is expanding, with majorities in some countries reporting regular use. However, there is a large digital divide: Access to digital sources is much higher in some countries than others, and is skewed in favour of wealthier, better-educated, younger, urban, and male citizens.”

According to Afrobarometer, Africa, as elsewhere, mass media face increasing opportunities and threats. New technologies have made it easier for producers to share content widely and cheaply, resulting in a proliferation and diversification of information sources.

It says broader populations can access content more easily and cheaply than ever before – and contribute to those discussions themselves – through call-in programs on vernacular radio stations, Internet news sites and blogs, and social media such as WhatsApp and Twitter.

“On the flip side, new competition and access to cost-free content threaten media organizations’ bottom lines. Consumer skepticism of media actors has skyrocketed as more people see media as propagators of falsehoods, bias, and hate speech, particularly when messages are critical of politicians or policies they support. Politicians – in democracies as well as authoritarian regimes – are more than happy to stoke this anger, which provides opportunities for governments to launch increasingly brazen legal and extra-legal attacks on media.

Prominent media watchdogs, such as Freedom House, the Committee to Protect Journalists, and Reporters Without Borders, have documented increases in government regulations, censorship, and even violence against media actors in Africa and around the world.

The latest round of the Afrobarometer survey raises a red flag for free-press advocates. “Popular support for media freedom – a majority view just three years ago – is now in the minority, exceeded by those who would grant governments the censor’s pencil.

“This warning flag also marks a paradox. On the one hand, many Africans believe that media in their countries have more freedoms today than they did several years ago. However, it is not clear that people view these developments positively. In fact, among citizens who see media freedoms as increasing in their country, those calling for increased government restrictions on media significantly outnumber those who support broad press freedoms.”

Afrobarometer notes that perhaps more encouragingly, those who see media freedoms as declining in their country are more likely to support freedoms than restrictions. “Either way, it appears that a substantial number of Africans are dissatisfied with the current state of the media in their country, at least with regard to the demand for and supply of freedoms.

“Even so, nearly all Africans turn to mass media for news.”

- Gibbs Dube

John Masuku: Journalists Should Stick to Basic Writing Skills to Avoid Circulating Fake News

Zimbabwean journalists have been urged to stick to basic news writing skills in order to avoid misleading the public or peddling fake news as authentic information. Veteran broadcaster John Masuku made these remarks ahead of this year’s commemorations of World Press Day on Friday. Masuku speaks with VOA Zimbabwe Service’s Gibbs Dube about this year’s theme c and media laws in Zimbabwe.

Gibbs Dube: We are commemorating World Press Freedom Day this Friday under the theme ‘Media for Democracy: Journalism and Elections in Times of Disinformation’. The focus is on democracy in times of fake news. What’s your take on disinformation and the circulation of fake news?

John Masuku: I’d like to encourage ourselves as media practitioners, journalists, to ensure that we are not the spreaders of fake news, because I’ve noticed that often times, on our platforms, on our chat groups, we tend to circulate fake news ourselves, instead of using the tools that we already know from our trade, in order to make sure that we sift all the fake news and only circulate amongst ourselves what is principle. So it is important that we play an important role as journalist to avert the spread of fake news.

Gibbs Dube: What do you think are the causative factors of journalists circulating fake news?

I think there are several factors, you know we are bored because the situation is never changing. We are also facing challenges in sustainability, and also, generally, the checks and balances that we were used to in the past, where we were proud of our profession as journalism, where people relied very much on us, we are now not taking that as seriously, and as a result, even some of our journalists are not writing stories after thorough research, so that it becomes very difficult to spread fake news.

You know if we run credible platforms people use them to verify if the facts are correct. So if something is spread out there, and you know if you check with VOA Studio 7, or if you check with the Voice of the People, you check with another platform, you get the correct information. But at times if we slacken in that direction, then there’ll be a lot of fake news coming from us.

So even encourage the membership organizations to continue what they’ve been doing, training journalists, and also retraining journalists and editors and running competition in order to create awareness about the danger of fake news, especially amongst ourselves as journalists and society as a whole.

Gibbs Dube: Now, in terms of laws, the government is saying that is actually transforming or dumping Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act (AIPPA) and other stringent laws. So what do you think the government will come out with? There are some fears obviously the coming laws may be worse than AIPPA, and others. What’s your take on that?

I think we should be involved. We should have full participation in everything that is being drafted or crafted, so that we don’t cry foul in future, when these laws are not in our favor. So now that the pronouncements have been made, and these laws are being changed, let’s write about them, let’s discuss them in our various programs, lets’ challenge them even through parliament, even though the ministry of information, let us be involved.

We have a tendency to leaving these to other parties and then when the laws are enacted, that’s when we write screaming headlines to say that we’ve been taken by surprise, we didn’t know what was going on and so forth. So I encourage ourselves as journalists that we are really following all that is taking place and also writing about it, so that there is no foul play as it were.

So as things stand right now, who is involved? Are we involved through our membership organizations? If we are not, let us be involved. Are we involved in writing about these issues that you are talking about? And not only talk about the fears, but let’s also talk about the content. What is it that is being changed from, to? Because others don’t even know what was there before, the content of the old, the draconian content that we’ve been always crying foul about, so we have to understand where we are coming from, and where we are going to and what advantage that has got for us as journalists.

So I really urge fellow journalists, fellow media practitioners that we be in it, and not only go by hearsay that this is going to happen, that government is going to do this, when we don’t have the facts on our fingertips.

Benin Internet Shutdown Repeats Pattern of Government Censorship Across Africa

When authorities in Benin turned off the country’s internet during parliamentary elections Sunday, they became the ninth African government to restrict access this year.

The outages last hours or days and may target specific services — or the entire internet.

Governments don’t often explain the outages, but when they do, they focus on the need for security and civil order. The shutdowns usually accompany protests, demonstrations and elections.

But data from The NetBlocks Group, a nonpartisan organization that tracks global internet freedom and monitors outages, indicate the serious economic and social impacts of even a short outage.

‘A blunt violation’

In Benin, a one-day shutdown costs the country $1.54 million, according to data compiled by NetBlocks and The Internet Society, a U.S.-based nonprofit organization focused on internet freedom.

In more populous nations, such as Ethiopia, those numbers can climb five times higher, even while internet adoption rates remain relatively low.

Benin’s outage lasted 15 hours and encompassed all internet services, including social media, according to NetBlocks.

Press freedom and human rights groups, meanwhile, continue to sound alarms about the impact of internet outages on journalists’ abilities to gather and report news.

“The decision to shut down access to the Internet and social media on an election day is a blunt violation of the right to freedom of expression,” François Patuel, Amnesty International’s West Africa researcher, wrote Sunday.

Gatekeepers

Citizens gain access to the internet via an internet service provider, or ISP. Each ISP acts as a gatekeeper to the internet, providing its subscribers access, but also, potentially, cutting them off.

In Africa, countries tend to have just one or two ISPs. For regimes intent on control, few ISPs makes it easier to turn off the entire internet for most of the population.

In contrast, thousands of ISPs provide access in the United States; shutting off the internet would require broad coordination, and cooperation across each independent organization.

In Africa, though, authorities often have an easy time controlling one or two state-owned ISPs. And governments have capitalized on that.

So far this year, Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Gabon, Mali and Zimbabwe have restricted internet access, according to Amnesty International. NetBlocks has observed additional disruptions in Algeria, Sudan and Egypt since January.

Freedom of expression

Journalists rely on internet access to do their work, and they tend to feel the effects of shutdowns more acutely.

Even partial outages can affect reporters’ abilities to communicate with sources, monitor events as they unfold and share news with audiences, in their countries and beyond.

Blocking internet access can affect freedom to assemble alongside freedom of expression. Protesters in Africa, and around the world, often use social media to organize.

But for governments experiencing tumultuous transfers of power, the internet can introduce unwanted volatility.

Most of the countries that have experienced outages this year, as in years past, have restricted access during elections or in the midst of protests and unrest.

World Press Freedom Day

A new report by an international media watchdog group says press freedoms deteriorated in 2019, fueled in part by increasing hostility toward journalists. How does this affect you? Plugged In asks the experts, "Why are press freedoms eroding in the United States and around the world?"

Raphael Khumalo: Democracy Can Thrive Where There is Fake News

Zimbabwe is expected to join other nations Friday in marking World Press Freedom Day being commemorated under the theme: Media for Democracy: Journalism and Elections in Times of Disinformation, focusing on current challenges faced by media in elections, along with the media’s potential in supporting peace and reconciliation processes. The 26th celebration of World Press Freedom Day is jointly organized by UNESCO, the African Union Commission and the Government of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. The main event will take place in Addis Ababa from May 1st to May 3rd at the African Union Headquarters. World Press Freedom Day was proclaimed by the UN General Assembly in December 1993, following the recommendation of UNESCO's General Conference. Since then, May 3rd, the anniversary of the Declaration of Windhoek, is celebrated worldwide as World Press Freedom Day. It is an opportunity to celebrate the fundamental principles of press freedom; assess the state of press freedom throughout the world; defend the media from attacks on their independence; and pay tribute to journalists who have lost their lives in the line of duty. In this first edition of a four-piece series on marking World Press Freedom Day, VOA Zimbabwe Service’s Gibbs Dube speaks with former chief executive officer of the Alpha Media Holdings, publishers of The Standard, NewsDay and The Independent.

Gibbs Dube: Zimbabweans are expected to commemorate World Press Freedom on Friday. The theme for this year’s event is: Media for Democracy: Journalism and Elections in Times of Disinformation. Talking about the media, democracy and disinformation. Do you think the media is doing the right thing?

Raphael Khumalo: It’s difficult to say what is right, because remember media is controlled and serves a particular purpose, depending on who owns that media and what their intentions are. And you also have fake news in there. It is possible and it’s much easier to deal with fake news and to identify the fake news where there is multiplicity of media. Whereas unlike in a situation where for example, there is monopoly over media, and monopoly is either held through those who own, who control…in other words, who are the ruling elite or connected to the elite. Then that becomes very difficult to decipher, which is fake news which is real news.

But in a situation where there is multiplicity of media for example, the situation is different. So yes, democracy will thrive in an environment where there is multiplicity of media, and it will still thrive, even where you still have fake news because people are well informed, have choice of what media to listen to, and therefore they are not easily bamboozled into believing one thing or the other. That is really the issue.

So the theme is quite appropriate, it particularly speaks to those societies where the plurality of media, whether you are talking about radio, in this case commercial radio, or you are talking about community radio stations, where we are still particularly in our environment where we are still stuck in the eras of the 60s where we have one broadcaster, ZBC, one TV broadcaster, ZTV, then you have serious problems.

And then of course someone will then say oh, there are these others – but look at the ownership structure, where do they go to? They go back to the center, so that’s where the issue is really.

Gibbs Dube: How is democracy enhanced in terms of having all these kind of fake news, because people actually believe what they read? It’s difficult actually to sift some of this information. So does it start from the journalists themselves?

Obviously Mr. Dube, it starts from journalists themselves, and number two, also it goes back to the populace themselves. The population will always go back and say, mmmm, if I have read it in this particular media, I am likely to believe it. And then, mmm, if it is this one, I think I need another source, to cross check. But remember as I said to you, where there is media is in a particular situation is controlled, or a large part of the media is owned by government or pro-government institutions, and there’s very little independent media there, it becomes very difficult for the population to actually believe is this fake news or is this for real. So I think this is where there is definitely a challenge in terms of dissemination of information.

And obviously when you have such situations, democracy does not thrive either. But look, fake news thrives in other environments. Check for example in the UK, talking for example in Europe. There is fake news that circulates there, but it doesn’t mean that democracy is not thriving. But like I said, the counter to it is the multiplicity of media channels that the people are able to listen to alternative and counter check and cross check.

But look if for example you listen and there was an article that came out which said during the cyclone Idai, for example, there was an earthquake, no one else outside the realm of those who said it, heard or felt the earthquake, but it was all just traditionalists, or those who were passing fake news as real news who started circulating such information to say that there was an earthquake that happened, at the same time that there was a cyclone, but nobody else heard it. But if you are there for the single source of information, then by all means you are going to be taken for a big, big ride.

Gibbs Dube: Media laws, do they actually affect the depth, the width and length of democracy? Do you think good media laws lead to better information being given to the public?

Raphael Khumalo: Dube, I will say to you that one of the major challenges if you operate in Zimbabwe. I will give my own personal experience. Over the year, I’ve made sure I’d read a South African newspaper, on a weekly basis. And every time you read a South African newspaper, you looked and you saw the depth of information, of just how many access the journalist writing the story has. Compared to the lack there of a journalist here. It speaks volumes about access to information and that access to information is not superficial. It happens because we have AIPPA (Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act) here and the South Africans don’t.

And that that speaks to just how much do the citizens know about what is going on, whether you are talking about in the army barracks, whether you are talking about in the police camps, how much are the journalists prepared to go and dig in, they won’t, because of the existence of the stringent laws, either, they are there in AIPPA, they are there in POSA (Public Order and Security Act) and various other restrictive legislation that make it difficult.

Do you think for example, the new book that came out in South Africa, Gangster State, would ever be written in Zimbabwe, here?

South Sudan Mourns Veteran Journalist

South Sudanese are paying tribute to veteran journalist and politician Alfred Taban, who passed away over the weekend in Kampala, Uganda.

Journalists who worked with him described Taban, 62, as a tireless advocate for freedom of expression in Sudan and South Sudan.

In 2000, Taban launched Sudan's first independent newspaper, the Khartoum Monitor, and later renamed it the Juba Monitor after South Sudan seceded from Sudan in 2011.

He was appointed a member of parliament for Kajokeji in the National Assembly in 2017, and unsuccessfully contested the governor's seat of the former Central Equatoria in 2010.

South Sudanese commentators on social media remembered Taban as a freedom fighter, statesman, liberator and hero.

Called freedom fighter

His uncle, Professor Taban Lo Liyong, one of Africa's most respected writers and poets, called his nephew a freedom fighter who criticized the government in Khartoum during the war, which led to South Sudan's independence.

"He did help in the war, and he did fight the war in Khartoum. He even saved some journalists and other people who were caught by the system for having pointed out where the wrong things are done," Lo Liyong said. "So, I am glad that Logune (Taban) had done his share of nation-building.''

Chaplain Kara Yokoju, head of development communications at the University of Juba, described Taban as a man who spoke for the voiceless.

"I remember him as being a fearless journalist who will tell the truth as it is, regardless of what the consequences (are). So, ever since he has been in Khartoum or even here (Juba), I used to come here and take pictures. Even when he was released from prison, I came here sometimes and had a chat with him. So, that is the memory that I will live with until the end."

Taban was repeatedly detained by authorities in Khartoum for criticizing former President Omar al-Bashir. He was arrested in Juba in July 2016 for demanding President Salva Kiir and First Vice President Riek Machar step down because, according to him, both leaders failed to implement the August 2015 peace agreement.

Anna Nimrano, editor-in-chief of the Juba Monitor, worked closely with Taban since the newspaper's launch. She said his impact on the media in Sudan and South Sudan looms large.

"When he left (the) media, I really noticed that it is difficult to get somebody like him, because if there are other things going wrong in the country, there is nobody who stands strong like Alfred. Even the time when he was the chairperson of AMDISS (Association for Media Development in South Sudan), when anything happened to the media houses or journalists, you would see Alfred come immediately and put it in (the) media. But when we compare with the times now, many things happen to journalists.There is nobody coming forward like Alfred."

Challenged other journalists

Irene Ayaa, an AMDISS official, fondly remembered the award-winning journalist.

"My favorite memory was when Alfred was having a meeting with AMDISS, and then he challenged us that we are cowards. He said for him, a journalist cannot be arrested and taken to jail and he is just enjoying his time at his home. He rather preferred him (Taban) to be arrested instead of a journalist."

In 2006, Taban won theNational Endowment for Democracy Award, cited as "one of the leading nonviolent voices of Sudan's dispossessed and marginalized communities, as well as an advocate for national reconciliation, human rights and democracy."

He also won Britain's House of Commons Press Gallery Speaker Abbot Award for "bravery in the face of personal risk, including torture, and for his commitment to bring to the wider world the horrors of Darfur."

A social media campaign has been launched to raise money to pay Taban's outstanding medical bills at the hospital in Kampala where he died, and to transport his body back to South Sudan for burial.

- VOA

World to Mark Press Freedom Day in Times of Fake News

World Press Freedom Day is this year jointly organized by the United Nations, Education, Science and Culture Organization (UNESCO), African Union Commission and Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia.

According to the U.N, the main event will take place in Addis Ababa, on 1-3 May at the African Union Headquarters.

This year's theme ‘Media for Democracy: Journalism and Elections in Times of Disinformation’ discusses current challenges faced by media in elections, along with the media’s potential in supporting peace and reconciliation processes.

World Press Freedom Day was proclaimed by the UN General Assembly in December 1993, following the recommendation of UNESCO's General Conference.

Since then, May 3, the anniversary of the Declaration of Windhoek is celebrated worldwide as World Press Freedom Day.

It is an opportunity to celebrate the fundamental principles of press freedom, assess the state of press freedom throughout the world, defend the media from attacks on their independence, and pay tribute to journalists who have lost their lives in the line of duty.