The deadly siege of the U.S. Capitol delivered a sobering lesson to Gigi Mei, who graduated last May from Columbia University in New York.

“Democracy is really fragile, and it takes a lot of efforts and energy,” said Mei, a 25-year-old from China. “And it needs people from all aspects to sustain, protect and practice.”

Mei was among dozens of U.S. immigrants or first-generation Americans who spoke with VOA after thousands of rioters surged past U.S. Capitol Police in an unsuccessful bid to block lawmakers from certifying Joe Biden’s election win over Donald Trump as the next president.

Like much of the world, these immigrants expressed shock at the Jan. 6 armed insurrection, which left five people dead, including a police officer. Some compared it to political violence in their respective homelands. They spoke of jagged partisan divides — deepened through the Nov. 3 election, voter fraud cases repeatedly rejected in state and federal courts, a fresh impeachment and threats of mayhem nationwide around Biden’s scheduled inauguration Wednesday.

Yet these immigrants also said they were confident democracy would prevail in America —with effort.

“We see the U.S. is spending billions of dollars … in different countries and different continents” to support democracy, economic development, civic education, human rights and more, said Mirwais Safi, who interpreted for the U.S. government in his native Afghanistan before coming to the United States on a special immigrant visa. “But we found that a lot of work is required inside the United States as well.”

Now Safi works for a northern Virginia nonprofit — focused on democracy and development.

FILE - In this Jan. 6, 2021, file photo supporters of President Donald Trump are confronted by U.S. Capitol Police officers outside the Senate Chamber inside the Capitol in Washington.

Uncomfortable reality

To Boukary Sawadogo, who teaches African film studies at the City College of New York, the scene of rioters storming the Capitol “seemed out of a Hollywood film” — not a reality he’d ever expected in the seat of American political power.

Sawadogo, raised in Burkina Faso, said it reminded him of mass protests in 2014 that forced out the West African country’s president, Blaise Compaoré, after 27 years. “Demonstrators took over the parliament, burned the building,” he said. The lawmakers “fled for their lives.”

U.S. lawmakers were rushed from their chambers, too, but returned within hours to complete the election certification on schedule.

Members of the group that took over the Capitol said they had a right to protest U.S. election results.

“We are there to demand the truth,” said Tuan Anh La, a U.S. Navy veteran originally from Vietnam. “It is impossible for us to accept a certain result when half the voters are in the limbo” over the Nov. 3 vote.

Electoral College ballot boxes are carried to the House of Representatives at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., Jan. 6, 2021.

Individual states took days, even weeks, to count ballots. In the end, Biden received 81 million votes; Trump got 74 million. In the determinative U.S. Electoral College, Biden defeated Trump 306-232 votes.

Vanndhath Man, who emigrated from Cambodia and works as a nurse in northern Virginia, said he didn’t believe the attack was premeditated — though some protesters came with bear spray, zip ties and other assorted items suggesting robust planning with malevolent intent.

“I think this mob or these protesters … never planned on it to be a violent act,” he said. “But when push came to shove, it ended up escalating into a trespassing or intrusion of Capitol Hill.”

The Capitol attack “was very personal to me,” said Osman Ahmed, 33, who had worked there for two U.S. senators from Minnesota. “As a staffer, you couldn’t get onto the Senate floor without screening,” he said. “… I know how secure and well-kept that building is.”

Ahmed left in 2019, joining a Minneapolis nonprofit to build community partnerships. He recoiled from onscreen images of the Capitol’s bloodshed, which he said brought flashbacks of his childhood in an unstable Somalia.

Ahmed praised “the police and the law officers who defended the lives of elected officials.” But he also said he was “concerned” that few of the overwhelmingly white rioters were arrested — at least initially. “That just really shows, like, the racial bias and all the society’s inequalities that exist. … And people of color — it would not be the same if it happened to them.”

According to a CNN analysis of Washington police data, 61 “unrest-related” arrests were made Jan. 6, compared to 316 on June 1, 2020 — the day Black Lives Matter protesters were cleared from streets near the White House before President Donald Trump emerged to stand for photos in front of St. John’s Episcopal Church holding a bible.

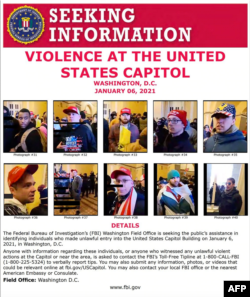

This image released by the FBI on Jan. 8, 2021, shows protesters in the US Capitol on Jan. 6, in Washington, DC. The FBI is seeking to identify the protesters.

More than 70 people have been charged in the attack and prosecutors are pursuing charges against at least 100 others, Michael Sherwin, the acting U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia, said at a Jan. 12 news conference. He said senior prosecutors also are looking into possible sedition and conspiracy charges, which could carry terms of up to 20 years.

That sounds comparatively mild to Jake Kim, who defected from North Korea and now is a student in Provo, Utah.

“To demonstrate is very democratic, but violence is shocking and unacceptable,” said Kim, who is in his 30s. In the United States, “people might be arrested and go to jail for a while. In North Korea, they would be executed.”

Freedom

All Democrats and 10 Republicans in the U.S. House of Representatives voted this week to impeach Trump for an unprecedented second time, accusing him of inciting an insurrection over the election results. The president has rejected any culpability.

He also has been banned or restricted by Twitter, Facebook and other social media platforms that accuse him of inflammatory comments.

“That’s unbelievable! We have freedom of speech,” complained Junior Bompeti, a 35-year-old software designer in Dallas, Texas.

Bompeti, who moved to the United States in 2015 from the Democratic Republic of Congo, founded the Facebook community Congolese for Trump.

He endorsed various lawsuits that unsuccessfully sought to overturn election results in multiple states that Trump lost. “We need to trust the process,” Bompeti said. “There are many allegations of fraud. The president keeps saying there was fraud.”

Solutions

Building trust and a better-functioning democracy requires respect, education and civic engagement, Bompeti and other immigrants said.

Political parties should “put aside” some of their differences, said Roba Bulga, a Brandeis University graduate student in conflict resolution who came from Ethiopia. He called this “a time of reconciliation, a time of bringing everyone together as a country.”

He urged looking beyond U.S. borders, saying, “A threat to democracy here can be a threat” to other parts of the world.

A protester lights an American flag on fire during a demonstration, Nov. 4, 2020, in Portland, Ore.

Thavin Keo also pressed for more civility, fretting over “a lot of hate everywhere. … Look at Portland. Look at Seattle,” she said, citing months of Black Lives Matter demonstrations last year that sometimes featured bloody clashes. The 67-year-old retired government contractor came as a refugee from Cambodia in 1981, settling in northern Virginia.

Republican and Democratic leaders “need to work together for democracy in this country,” she said. If not, “it’s not going to work out.”

Civic engagement is important to U.S.-born Pahniti (Tom) Tosuksri, who spent part of his childhood in his parents’ native Thailand and works for a nonprofit affordable housing program in Cleveland, Ohio.

He volunteered as a poll watcher in the November elections and wants to get “more involved … more aware of our local elections,” he said.

He also intends “to encourage folks” to do the same and learn more about local candidates and issues. When voting, “it’s not just the president, it’s not just the Senate, it’s also everything in between that we have to be aware of.”

Immigrants, especially those who have gained citizenship, have responsibilities, said Meron Semedar, a 34-year-old originally from Eritrea and now an adviser to African scholars at the University of California-Berkeley.

“I encourage every single immigrant community to go out there to exercise their rights,” from completing census data to casting a vote if eligible, Semedar said.

“It’s a responsibility, it’s a duty, and we should respect it, we should honor it. But also we should play our part in keeping the democracy flourish[ing],” he said. “And we should also teach similar things to our children. … It has to pass from generation to generation.”

President-elect Joe Biden speaks about the COVID-19 pandemic during an event at The Queen theater, Jan. 14, 2021, in Wilmington, Del.

To Sonam Zoksang, a small business owner in New York’s Hudson Valley, “the democracy has shown strength, but it needs protection.”

Born in Tibet, he came to the U.S. in 1995 via Nepal, where his parents fled after China occupied their motherland.

He said he looked to Biden, the incoming president, to deliver on his message of unity and healing.

“I believe this new administration and some good Republicans can work together. The world is looking up to America.”

This report includes contributions from multiple VOA services: Afghan, Cambodian, English to Africa, French to Africa, Horn, Korean, Mandarin, Somali, Thai, Tibetan and Vietnamese.